Mumbai has seen countless protests, but the late-August agitation led by Manoj Jarange-Patil was different. Promised as a peaceful sit-in, it swelled into a massive rally that paralysed the city’s heritage district. Azad Maidan overflowed with protesters, traffic near CSMT and JJ Marg came to a halt, and life for ordinary Mumbaikars was disrupted.

Within days, the Maharashtra government issued a Government Resolution (GR) on 2 September 2025 allowing Marathas with proof via the Hyderabad Gazetteer to obtain Kunbi caste certificates and claim benefits under the OBC quota. Instead of calming tensions, it sparked fresh divides—splitting Marathas and angering OBC groups who saw it as an intrusion into their share.

Do all Marathas really want reservation?

An uncomfortable question persists: do ordinary Marathas truly want quotas, or is the agitation driven by leaders and politics? Traditionally, Marathas were a dominant caste—landowning, politically central, and socially influential. But recent decades have weakened that dominance.

For young Marathas in rural areas, reservation feels like a lifeline—offering access to education, jobs, and security.

Roopa, senior leadership from a global IT company, reflects on the broader context, “Social equality is the reason that Marathas are flexing their collective muscle and demanding this. From personal experience it has been a painful process to watch less meritocratic candidates get ahead in life. Hence, demanding this privilege for yourself as well is the logical fall out. However, reservations never solved any problems. Class & social systems still exist everywhere in the world. So, what is the question we are trying to solve? If it is uplift meant of the Society's weaker sections then….

Define what we mean by ‘weaker sections’. The definitions have changed over 70 yrs. societal structure has changed over the years. All castes have sections of its population that needs a boost since it doesn’t have the means to encourage the talent that exists. So, if we decide to address these ‘weaker sections’ across the board the common denominator is economics. Most people will agree to this definition of ‘weaker section’. But will this give rise to another raft of economic offences to ‘prove’ your eligibility?

Hence implementation process of the commonly agreed ‘definition of weaker section’ also needs to be debated. Would tax rebates for the rich for sponsoring such candidates work?

What is imperative though, is that a change is needed from the current approach & definition."

Kunbi Conundrum

The September 2025 GR appeared to offer a shortcut, those with proof of Kunbi ancestry in documents like the Hyderabad Gazetteer could obtain caste certificates and directly enter the OBC quota. But the so-called shortcut has created chaos instead of clarity.

On 18 September, the Maratha Kranti Morcha (MKM) rejected the move outright, declaring that “Marathas and Kunbis are separate castes” and called the GR “blatant cheating” that undermined their demand for an exclusive quota.

On the other hand, OBC leaders like Chhagan Bhujbal have warned that bringing Marathas into the OBC fold is “playing with fire.” In mid-September, Bhujbal even presented examples of tampered Kunbi certificates and demanded a committee headed by a retired judge to scrutinise all such documents.

The result? More fractures—within the Maratha community, between Marathas and OBCs, and across Maharashtra’s political spectrum.

Law walking on thin ice

Earlier this year, the Maharashtra legislature passed the SEBC Act, 2024, granting Marathas a 10% quota in education and jobs, citing “exceptional circumstances” like poverty and farmer suicides.

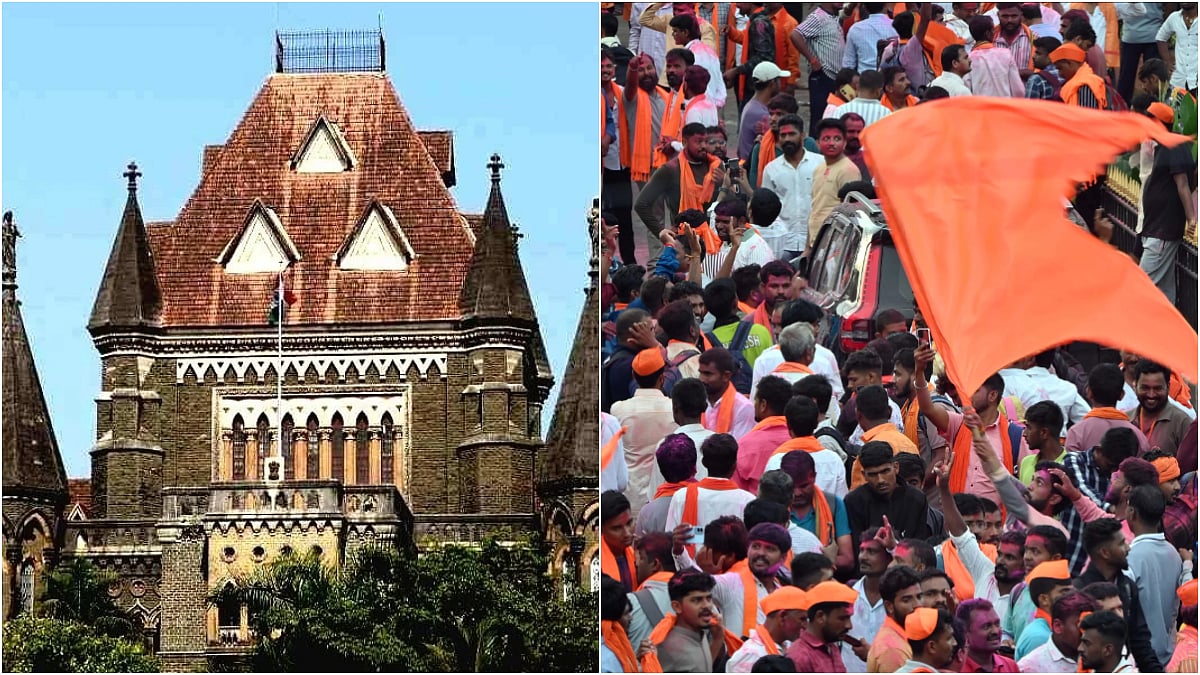

Yet, the law stands on shaky ground. In 2021, the Supreme Court struck down a similar Maratha quota for breaching the 50% cap and lacking data. The 2024 law is already under challenge in the Bombay High Court, which has only allowed it to function on an interim basis.

In September hearings, the state’s Advocate General clarified that the GR and the SEBC Act are independent provisions—though both face legal tests. On 18 September, the High Court dismissed a PIL challenging the GR, ruling the petitioner was “not an aggrieved party,” and warned against multiple litigations.

Mihir Gheewala, a criminal lawyer practicing in the High Court at Bombay for 30 years, Notes, “though reservations have a sanction of the constitution, they cannot cross the basic fundamental rights guaranteed under Article 14 of the constitution, which is a safeguard against discrimination. What I mean by this is that any further reservation will only become counterproductive and be arbitrary. The measure of backwardness of a members particular community, which became part of the scheduled tribes/castes, was their historic racial discrimination and unfair treatment. A community which has not been discriminated unfairly and adversely solely based on their birth in that community, cannot claim reservation under the constitution. That’s my view.

Reservation of jobs is not the answer to uplift the backwardness of a community which has not been historically discriminated against. To uplift such people, there must be special schools and education institutes to raise them to a proper playing field. Unmitigated reservation to all and sundry will act counterproductive and the meritorious candidates will be discriminated against in violation the principles of Article 14 of the COI. Reservation which leads to dip in productivity and efficiency in admiration and government services is in violation of the Fundamental Rights of a citizen guaranteed under Article 21 of COI. Reservation is an exception when certain criteria is satisfied. It cannot be a new normal.”

What constitution intended

The makers of the Constitution saw reservation as a temporary corrective measure, designed to uplift the most disadvantaged sections of society. The idea was to review the policy after 10 years, extend it only if necessary, and eventually phase it out.

75 years later, that vision seems almost forgotten. Instead of reducing dependence on quotas, socially and politically dominant communities—Patels in Gujarat, Jats in Haryana, and now Marathas in Maharashtra—are demanding inclusion. The original aim of helping the most marginalised has been overshadowed by competitive claims for scarce state resources.

Why is reservation still needed?

When India became independent, the hope was that a few decades of affirmative action would end caste-based disadvantage. Yet reservations remain central to Indian society because caste itself endures. It still shapes social mobility, land ownership, marriage alliances, and power structures.

Education and jobs—the main ladders of opportunity—remain unequally distributed. A Dalit or tribal child often begins life with poorer schools, fewer networks, and the stigma of caste. For them, reservation is a bridge, not a privilege.

Meanwhile, India’s economic challenges have intensified the demand. With shrinking government jobs and rising competition, communities see quotas as the only assurance of stability. This explains why even dominant groups like Marathas feel left out. On 17 September, five Marathwada districts began issuing Kunbi certificates to Maratha youth on Liberation Day—showing how eagerly communities pursue any path to reservation.

Reservation today serves two purposes: correcting historical injustice and cushioning present insecurity. Its persistence after seven decades highlights not just caste but also India’s failure to provide equal-quality education, healthcare, and jobs.

Divya Rai, a 24-year-old working professional, shares her experience, "In today’s urban setting we don’t really need reservations. Speaking as a general category student, I’ve seen how unfair it can feel. I scored 88-89% but couldn’t get into my dream college because the cut-off for general students was 90%. At the same time, students with 50–75% marks got admission through the reservation quota. Then they also get away with paying less fees, even those who come from good financial background. While, at times, students like me from the general category struggle to pay fees due to monetary issues.

That makes me wonder, what is our fault in this as a general category? Just because we are an open category that doesn't mean we have to suffer. Why are we penalized for something we cannot control?

I understand reservations were meant to uplift disadvantaged communities, but right now they often end up creating more divides by labelling people as SC, OBC, or general. I believe opportunities should be based purely on merit on effort, skill, and hard work. If we all earn our spot fairly, without any labels, it would create a truly equal and competitive system."

Poverty or caste?

This brings us to the heart of the debate: should caste remain the basis of reservation, or should poverty take precedence?

The 103rd Constitutional Amendment in 2019, creating a 10% quota for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) irrespective of caste, was a major shift.

Supporters argue poverty is the most accurate marker of disadvantage—why should a poor upper-caste child be denied help while a wealthy OBC or SC candidate benefits? 26-year-old Megha Pawar feels, “ India should reconsider its reservation policy. While caste-based quotas addressed historical injustices, today economic criteria could ensure benefits reach the truly needy. In Maharashtra, shifting to economic-based reservations might reduce caste tensions, but care is needed so that marginalized groups don’t lose support. A balanced model combining social and economic factors could uphold equity.”

Shrushti Bhoite, 23 year-old, shares her view "As someone from minority and low income homes, I would say education for me was very easy and that it isn't possible for everyone to experience the same, it'd be better if the reservations are extended to economic and financial criteria as alot of people struggle for good education taking in mind their financial conditions. So in my opinion I say we need a shift towards economic criteria."

Critics counter that poverty and caste exclusion are not the same. A poor upper-caste person may lack money, but they do not face systemic discrimination in schools, jobs, or social life. Reservations, they argue, are meant to redress structural injustice, not just income inequality.

Sameer Gudhate, World Record Holder Book Critique, observes, "The Maratha agitation and the Kunbi certificate push reflect how caste quotas have become less about upliftment and more about political bargaining. Reservation, once meant as a temporary corrective, has expanded endlessly, fuelling new agitations instead of resolving inequalities. Seventy-five years later, India must ask: does caste still justify preference, or should economic need guide support? Shifting to economic criteria would ensure help reaches the genuinely disadvantaged, regardless of birth. In Maharashtra, it could reduce quota wars, but only if applied firmly and fairly. Without this change, society risks deepening divides where opportunity is claimed, not earned."

The next chapter

The Maratha agitation and the government’s patchwork responses reflect a larger national dilemma. Can India move beyond caste when caste still dictates privilege and exclusion? Should poverty be the new benchmark? And how sustainable is a system where quotas keep expanding but existing beneficiaries fear dilution?

The Bombay High Court’s hearings in October will test the constitutional validity of both the SEBC Act and the GR. The real challenge is unresolved: how to balance caste justice with economic fairness, and how to build a society where opportunities are abundant enough that communities no longer fight over them.

As a younger-generation Maratha, I understand my community’s frustration. There is a genuine sense of being left behind. But more quotas alone cannot solve this. Unless India tackles unemployment, unequal education, and weak economic growth, the reservation debate will keep returning—again and again, like an unfinished chapter in our democracy.