Title: Gram Chikitsalay

Director: Rahul Pandey

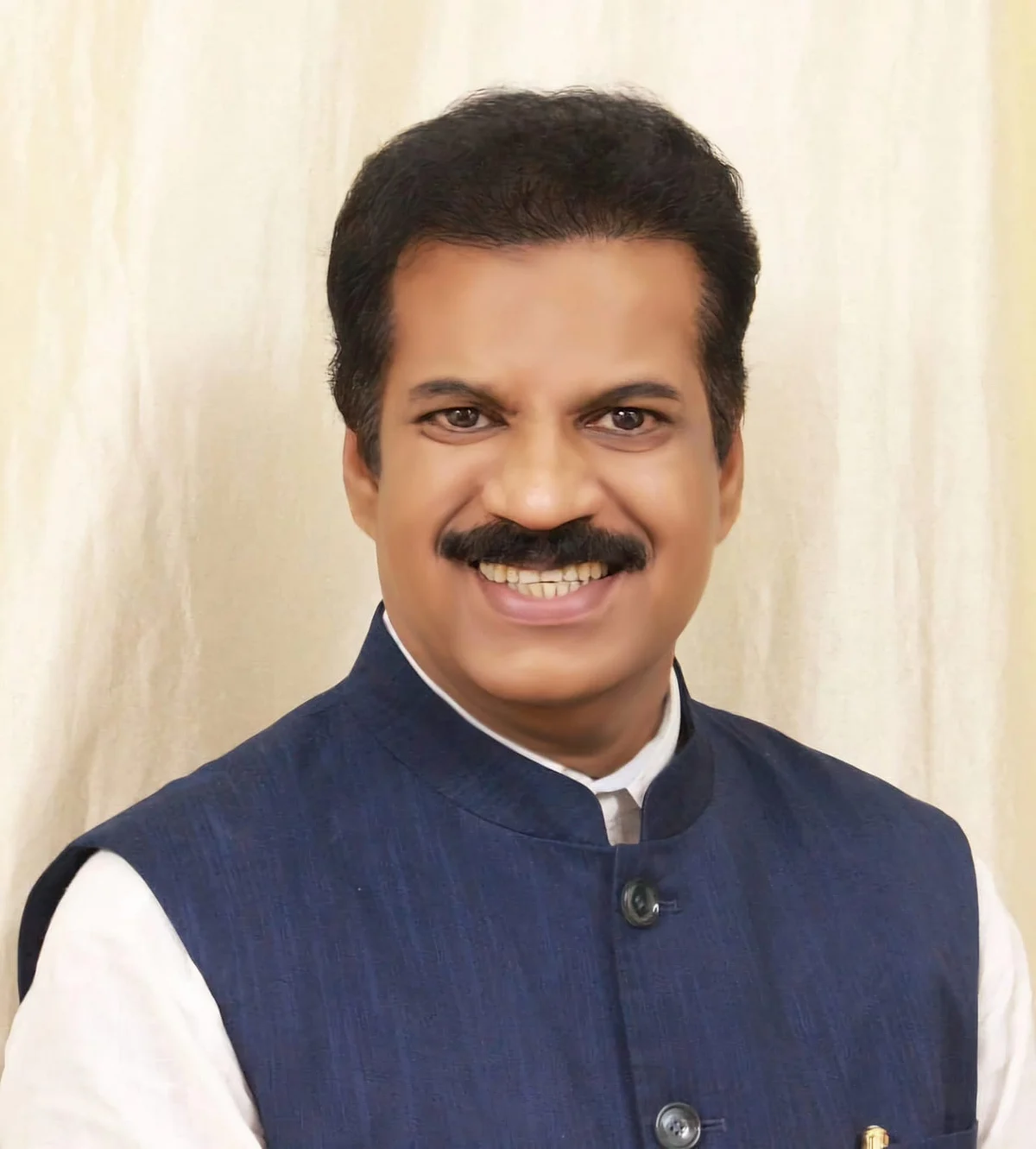

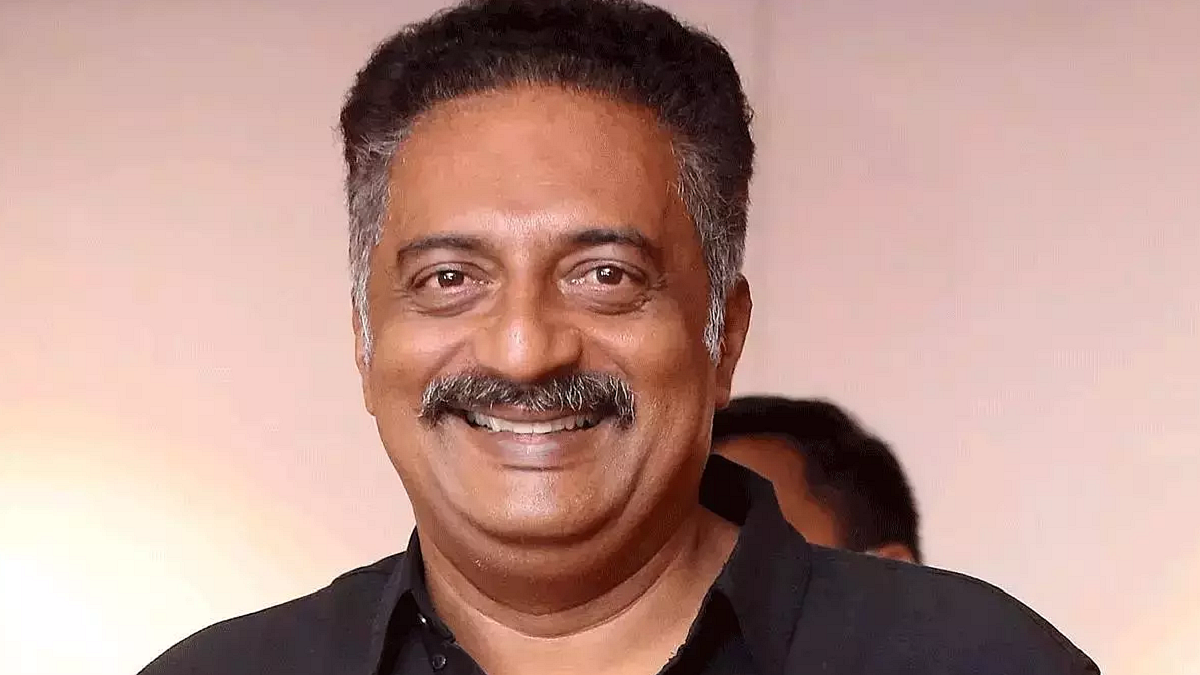

Cast: Vinay Pathak, Amol Parashar, Anandeshwar Dwivedi, Akash Makhija, Garima Vikrant Singh, and others

Where: Streaming on Prime Video

Rating: 3 Stars

Gram Chikitsalay—meaning ‘village clinic’—is a wry, heartfelt take on India’s ailing rural healthcare. From the makers of Panchayat, it trades red-tape offices for a defunct PHC in fictional Bhatkandi. An idealistic doctor arrives armed with hope and a stubborn sense of purpose. The village, however, prefers fake prescriptions and absent doctors.

With humour stitched into its narrative and a realism that never feels forced, the series offers a tender, if occasionally laboured, portrait of grassroots India. It’s sincere, satirical, and quietly observant—though by episode five, the narrative does begin to wheeze a little.

We meet Dr. Prabhat Sinha, played with earnest charm by Amol Parashar—a Delhi-bred gold medalist whose idealism arrives on Vishwakarma Pooja, the day no one works. His clinic? An abandoned structure marooned in a field illegally farmed by Ram Avtaar Singh (Akhileshwar Prasad Sinha), a gloriously cantankerous drunk. What follows is a series of frustrating encounters with apathetic villagers who prefer quacks, corrupt men lurking in the shadows, and bureaucratic inertia thick enough to slice with a rusted scalpel.

The supporting characters—compounder Phutani (Anandeshwar Dwivedi), ward boy Gobind (Akash Makhija), and nurse Indu (Garima Vikrant Singh)—propel the narrative with pitch-perfect performances. They don’t act rural, they are rural, embodying that resigned cynicism towards government schemes and new officers with just the right amount of theatrical understatement.

The writing is sharp without being flashy. Dialogues are unvarnished, grounded in a kind of realism that doesn’t scream for attention but gently elbows you to notice. Dr. Prabhat’s resolve to make the PHC functional is both noble and naive, and his moral compass, though slightly too magnetic north at times, is never unbearable. We get peeks into the rot: medicines being siphoned, quacks like Dr. Chetak Kumar (a reliably slippery Vinay Pathak) thriving, and netas sniffing out opportunities to co-opt honest work into their charade.

However, like a slow-drip IV, the pacing begins to falter. By episode five, the narrative stretches thin, like a khadi kurta tugged one size too far. What began as a slow-burning satire on the rural medical apparatus starts circling its symptoms. The diagnosis is clear: the series needs narrative adrenaline to maintain its early pulse.

Inescapably, Gram Chikitsalay invites comparison to Panchayat, that other meditative series on rural absurdity. While Panchayat is more polished in its wit and character arcs, Gram Chikitsalay dares to be more biting.

Cinematographer Girish Kant gifts the series its most redeeming visual vocabulary—fields that stretch like time itself, winding village paths, and expressions captured with an intimacy that makes you feel like an eavesdropper. The cast slips into their roles like worn chappals—easy, real, and lived-in. Even the loud background score somehow works, echoing the chaos beneath Bhatkandi’s hush.

Credit must go to editor Chandrashekar Prajapati for keeping the seams invisible. If only the plot had his same discipline.

Ultimately, Gram Chikitsalay offers a valuable prescription: rural India is not just scenic—it’s seething. The series may not have the sharpest scalpel, but it certainly knows where it hurts.