Philanthropy is a growing sector in India, but SVP's approach to do collaborative philanthropy with people of all classes and all capabilities is a very different model. How did you come up with that idea?

SVP started in 2012. In 2013, the law came in, making CSR a large donor pool. But it's not going to be the ultra-high net worth individuals who will make a difference—it is the 100 million people who can actually give some money somewhere. I said, "Let's start with the one million or the two million that can give today. And over time, that number will grow." A 100 rupees from a million people is far more than five HNIs giving the same money, because the impact it has on society is very different. When a few people give, I value their giving, but it's not a movement. But when many people give, it becomes a movement. And that's what SVP is about.

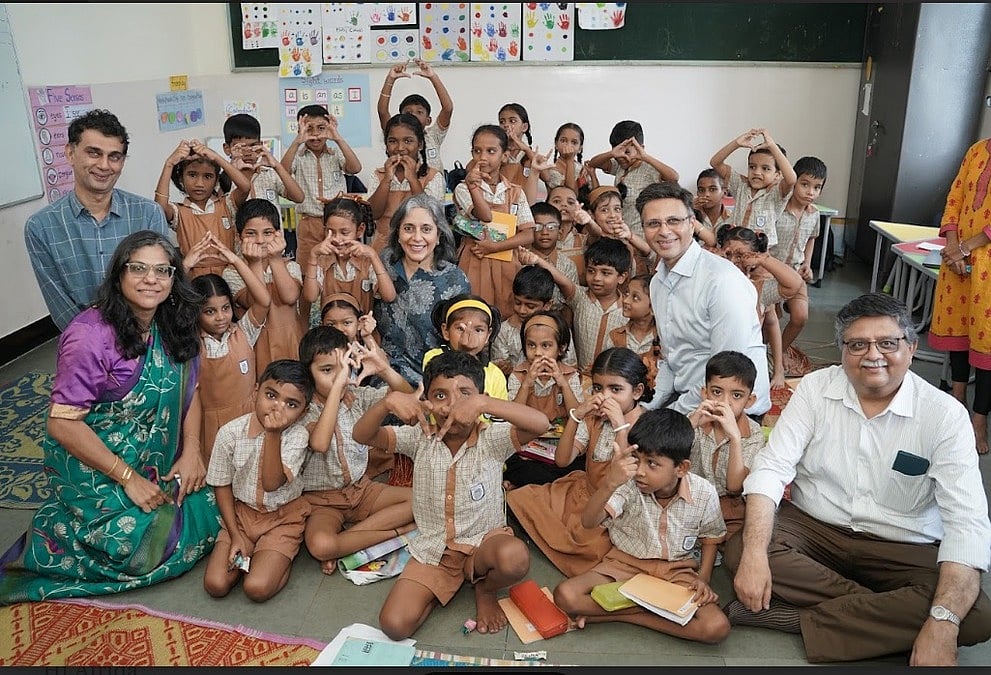

We are now about 750 colleagues and all of us are doing our small way of enabling our own communities to really get better. The SVP model is one where you give a little bit of money, but you give a lot more of your wisdom and your time.

There is no structure at SVP to say you have to do A, B or C to become an effective partner. You can choose to be an active, engaged philanthropist by working with a not-for-profit. You can choose to observe and contribute when required. You can choose to engage within the institution in a lot of different ways. It's a very flexible approach to giving your time, wisdom and money.

Do you see that young people now have a culture of giving? Do they have a cause in mind or do they just have a surplus and want to give?

My children are 29, 23 and 19. When in 2018, I walked up to them and I said, "I'm thinking of taking a pledge to give 50% of my income during my lifetime or in my will," those three boys gave me the courage to say that I don't need to leave anything for them. I might, but I don't need to.

A lot of young people are giving now because of two reasons. They have huge confidence they don't have to worry about surpluses. They've seen their parents go through a generation where there was more than they wanted, and they said there will always be more than we want, so we can give early. Under the Living My Promise initiative we have quite a few people in their thirties pledging to give away half their wealth.

If you look at the NGO ecosystem, even with SVP and the NGOs we work with, many are under the age of 35. The people in the social sector who have come out from Teach For India, from Akansha, they’re all in their thirties. To me, that's giving. The heroes are not the donors. The heroes are actually the receivers, the people implementing programmes.

I get very concerned when there's a mismatch of power between donor and donee. And I get concerned about it because the checkbook doesn't define the destiny of India. The doers define the destiny of India. To me, that's whom we should focus on.

You've spoken about your professional career that was rooted in a culture of authenticity, relationships, and of leadership with kindness. Was that one reason to select this very unique path within philanthropy?

There's a story here. It's one of those pivotal moments in my own life that happened accidentally. In 2012, I was at a retreat, and I was thinking about the next 10 years of my life. It was a facilitated workshop with an external facilitator.

I'd had the good fortune of many good things happen in my life at that point of time. I had just turned 50. I said to myself, "What can I do more for myself, but also for the community?" And I said, "The one good thing that I've had is I've had the blessings of many and the goodwill of many. Can I transfer that goodwill and leverage it for the social sector?" You won't believe it—five minutes after that, I got a call from Ravi Venkateshan, the founder of SVP India, and he asked me to join the board.

It was really a manifestation. That was the starting point of my philanthropy journey, but when I look back in time, my grandfather was a huge giver. In fact, when he passed away suddenly, while very young, he had no money in his bank account because he had given most of it away. His wife and his children were very young, and they had to start from zero. My grandfather was the first Indian PhD student who had done sugar technology from Berkeley. When he came back, he was also helping a lot of people. So I think somewhere along the way, whether it's my parents, whether it's my grandparents, I think the desire was there but it was never unleashed.

This is what SVP has given me, my platform to start my journey.

Has philanthropy as a sector in India has come of age enough to go beyond projects to achieving systems-level change?

For many years of my life, from 2012 to about 2017-18, I used to fund a lot of opportunities in the capacity building area. If you ask me to fund 100 meals, I will do it, but that won't be my core. I would say, "Can you build five kitchens for me to feed a thousand people?” So I like to go to the capacity building side and not necessarily the project side. That's me, as a human being. I'm not saying that's the only way. When I got engaged with The Convergence Foundation, they talked about 5 to 10 years’ patient capital to drive systemic change. I didn't understand what that meant, but today, six years later, I think it's come of age.

Along with Ashish Dhawan (founder of The Convergence Foundation) and his team, we're trying to get people to recognise that there's no point in solving today's problems. We've got to try in some ways to eliminate today's problems by driving a change in the way system change happens.

So it’s happening, but is it happening at the quantum or the speed at which I want? Probably not. But give it time. In 2012-13, if anybody had told me that the sector today would have so many unicorns, so many outstanding not-for-profits, I would have said they’re smoking something. So I think 10 years from now, I believe systems change will come of age.

Are there any things that drive you to tears, that make you feel that a problem must be solved very urgently, today?

I actually haven't applied myself to a cause versus a purpose. To me, the thing that makes me tear up, or which makes me get really upset or agitated, is when people don't believe that we have outstanding not-for-profits in the sector.

Trust in the sector is what I think is the biggest hurdle towards growth. People would unflinchingly say, "I'll buy 100 Apple shares," or, "I'll buy 100 shares of Unilever," If I go and say, "Can you give me a lakh for this initiative for this not-for-profit?" they will ask me five questions.

I think a time must come when that question is not asked but instead they ask, "How will you make it work better?" That is a question I like. "Okay, I'm going to give you one lakh, I might give you even two lakhs. Tell me, how can you make that work better and how can I help you make that work better?" That's when the sector changes.

We shouldn't make working for our community an option. Volunteering time in a not-for-profit cause or an ecosystem is something we should do every day or every week.

I think all causes are equal, whether it's animal welfare or education. What I want is to be an evangelist to try and drive the cause of philanthropy, not the cause of a sector. I want to get more and more people to recognise the social sector as an industry—today it's perceived like a cottage industry.