‘Jis mein jaltaa huun usi aag mein jalnaa hai tujhe

uth merii jaan mere saath hii chalnaa hai tujhe’

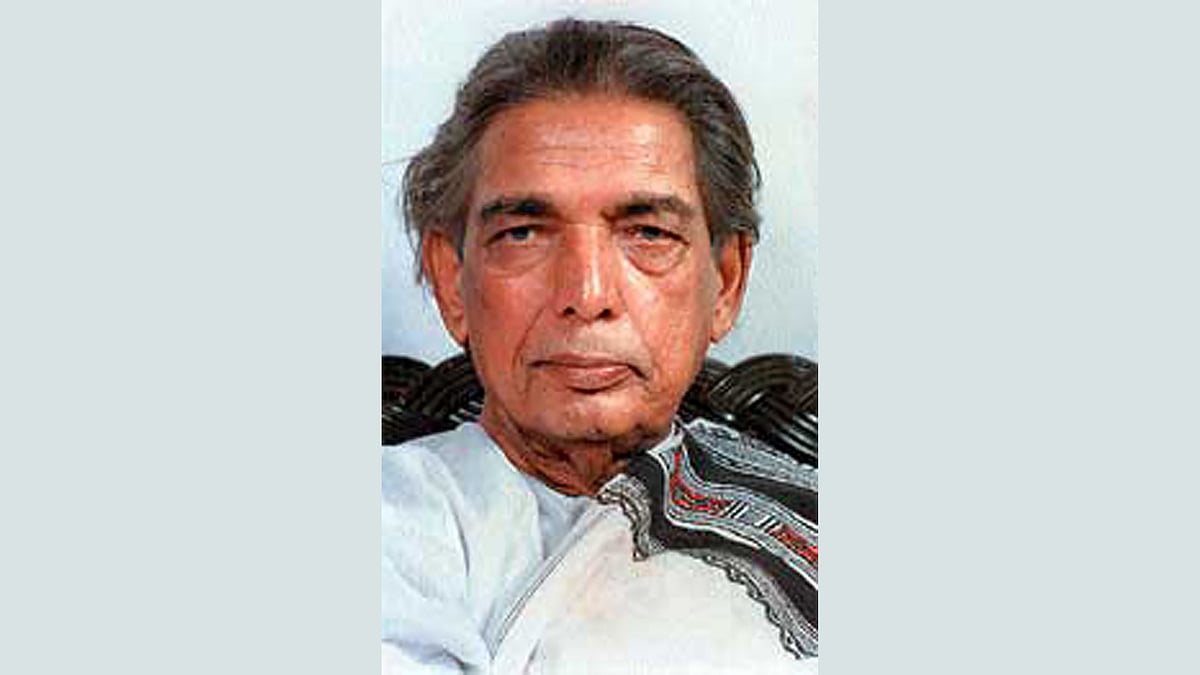

--Kaifi Azmi

January 14 marks the 106th birth anniversary of Indian poet Kaif Azmi. To commemorate this special day, Urdu Markaz, a literary and cultural organisation working for the promotion of Urdu language in India, is conducting a walk showcasing Azmi’s relationship with Bombay — today’s Mumbai

Bombay beckons

Kaifi Azmi, hailing from Mijwan, a small village in Uttar Pradesh, was only 15-years-old when he came to Bombay. Though born in a well-to-do family, Azmi was always inclined towards the welfare of the less fortunate.

“Abba came from the zamindar (landlord) family. His mother used to say that at the age of seven he would not wear new clothes on Eid because the farmer’s children could not afford new clothes,” says Shabana Azmi, veteran actress and daughter of Kaifi Azmi. “I think that led him to the communist party. The mandate of the party was to work for social justice, was to work for the labourer, the farmer and for the equality of women. That was in his heart and he could be honed in the communist party. He was a multifaceted person. Jisko kehthe hai na reedh ki haddi woh communist party hai (Communist party was his spine).”

She tells about his journey from Mijwan to Bombay. “Strangely, his parents put him into Madarsa. In the first three months, he got the students together and went on a strike against the maulvis. That’s why he was thrown out. Then he went to Kanpur where he worked with the cobblers and shoemakers there and then he started writing his revolutionary poetry there which was noticed by Ali Sardar Jafri and Sajjad Zaheer. They called him to Bombay to join the communist party. He started writing for their paper Qaumi Jang. After that, he was completely committed to it.”

Progressive Writers Association

Zubair Azmi, director of Urdu Markaaz, talks about how the Progressive Writers Association found home in Bombay. “They felt that Bombay had the congenial atmosphere for their movement. Madanpura had ancillary cotton industries. It is where the labour movement was started and Kaifi Azmi joined the movement.”

The walk organised explores the Madanpura, the old Communist Party office, Khada Parsi monument, and other locations that made an impact on Kaifi Azmi’s life.

Azmi found his calling in Bombay and the city shaped his writing. “His relationship with Bombay most certainly shaped him. One of his most evocative poems, Makaan, is about the plight of the construction workers. Who with their sweat and blood builds these huge buildings and when it is complete the very labourer who made it is thrown out because the chaukidar is put instead and he can’t enter the very building that he had made. So the poet calls out and says: ‘Aaj ki raat bohot garm hawa chalti hai, Aaj ki raat na footpath par neend ayegi. Sab utho, mai bhi uthu tum bhi utho, tum bhi utho. Koi khidki iss hi deewar main khul jayegi’,” Shabana shares. “So he is exhorting that khidki he is talking jo khul jayegi (will open the windows), is for social justice and against all kinds of social ills.”

Communist Party

Kaifi Azmi dedicated most of his time to the communist party. Staying in the humble home of Madanpura of Mumbai, he lived very close to Girangao which was a hub of textile mills. The Communist party was at the Red Flag Hall in Khetwadi. “He was the foot soldier of the communist party. He spent all his time with the labourers and the construction workers of Madanpura. He immersed himself in the cotton mill workers,” tells Shabana.

IPTA

He was made in charge of the Indian People’s Theatre (IPTA). “My mother (Shaukat Azmi) expected that he would be asked to leave the Progressive Writer’s Association because he does so much work. But to everybody’s surprise, the communist party asked him to take charge of IPTA of which he had absolutely no experience.”

She adds, “So when abba was given that job he did many many things that were long far-reaching consequences. He started an inter-collegiate drama competition. He was completely untrained but because he was a people’s person he thought that theatre should go to people. So he went about organising plays in which they would go to mohallas and perform there. They would go to areas where labourers worked. IPTA believed very sincerely that art should be used as an instrument for social change.”

Mushairas and theatre days

Shabana Azmi talks about the early days when Kaifi Azmi used to take them to the recitals.

“When ammi wasn’t there, abba used to take baba and me to mushairas. Because we could not afford a maid or anything. So we used to go to sleep on the stage behind those big gaav takias (pillows). And we got used to the fact that there was a lot of clapping then it meant that abba was reciting. So we would open our eyes sleepily and say that abba was reciting. And we would go back to sleep. So that was not a strange and unfamiliar situation.”

She talks about days when she could sit and listen to poets when they came home, “Then there were many progressive poets that were house guests with us like Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Firaq Gorakhpuri, Josh Malihabadi, and Begum Akhtar used to come. A lot of these people used to come to our house. There was no glamour but what I used to find fascinating was the Urdu language, the sounds of their voices behind the curtains. Then abba would call me and make me sit there and say you can sit for as long as you want provided that you will not bunk school because you were sleeping late. We were treated like adults. And, our opinions were invaluable.”

Cosmopolitan city

Kaifi Azmi’s Bombay is one where the city’s people live in harmony, where there is equality amongst the rich and poor, the industrialists and the labourers, the men and women.

Shabana Azmi talks about a Bombay she wishes never changes, “It’s cosmopolitan nature. In Mumbai, it is perfectly possible for you to go to a party where somebody is wearing diamonds and you can be in Khadi Kurta and Kolhapuri Chappals. It would not raise any eyebrows.”