The Centre has finally broken its prolonged silence on the next national census by announcing that the exercise will be completed by March 2027. While this sets a broad timeline, the exact dates will become clear only when the notification under the Census Act of 1948 is issued by the middle of this month. This will be the first census in 16 years—a glaring delay given that such a crucial exercise is mandated to be decennial.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic offered a temporary justification, it hardly explains the years of administrative inertia that followed. The upcoming census will be significant for several reasons. Most notably, it will be digital, employing the latest technological tools for faster and more accurate enumeration.

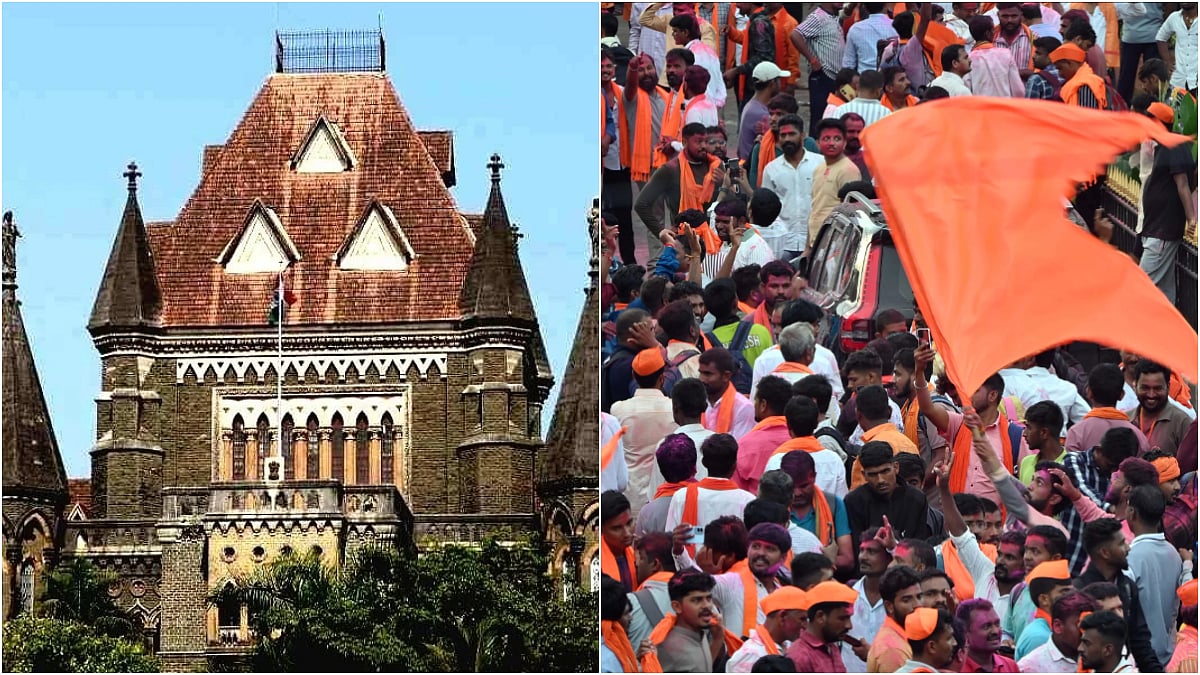

More crucially, for the first time since the British-era census of 1935, caste data will be comprehensively recorded. Until now, only Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes were counted separately. This time, people will be asked to disclose both their religion and caste, recognising that caste categories can vary in socio-economic status from state to state.

This return to caste enumeration underscores a sobering truth: despite 78 years of independence, India remains deeply mired in caste consciousness. While it may seem regressive to some, the reality is that policies like reservation are caste-based, and elections are routinely fought on caste lines.

Political parties, including the BJP, often field candidates based on constituency caste equations—despite espousing the idea of a casteless society. The BJP finds itself in a bind. It had to yield to growing demands for caste enumeration, especially after states like Bihar, ruled by one of its allies, conducted their own caste census. Acknowledging caste data is no longer optional; it has become a political necessity.

Another major issue that will resurface post-census is delimitation—the redrawing of parliamentary constituencies based on updated population data. So far, delimitation has been kept in abeyance to prevent punishing southern states like Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Karnataka for their success in controlling population growth.

A new delimitation based on updated figures would likely boost the representation of populous northern states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, further skewing political power toward the Hindi heartland. Interestingly, the new Parliament building was designed with additional capacity—widely seen as a preparatory step for future delimitation.

Despite its political complications, the census is a much-needed and welcome step. It will provide the government with the data necessary to ensure that development is inclusive and resource allocation is fair and evidence-based. The real test lies in how honestly the data is collected and how responsibly it is used.